Most people have more to do than time to do it.

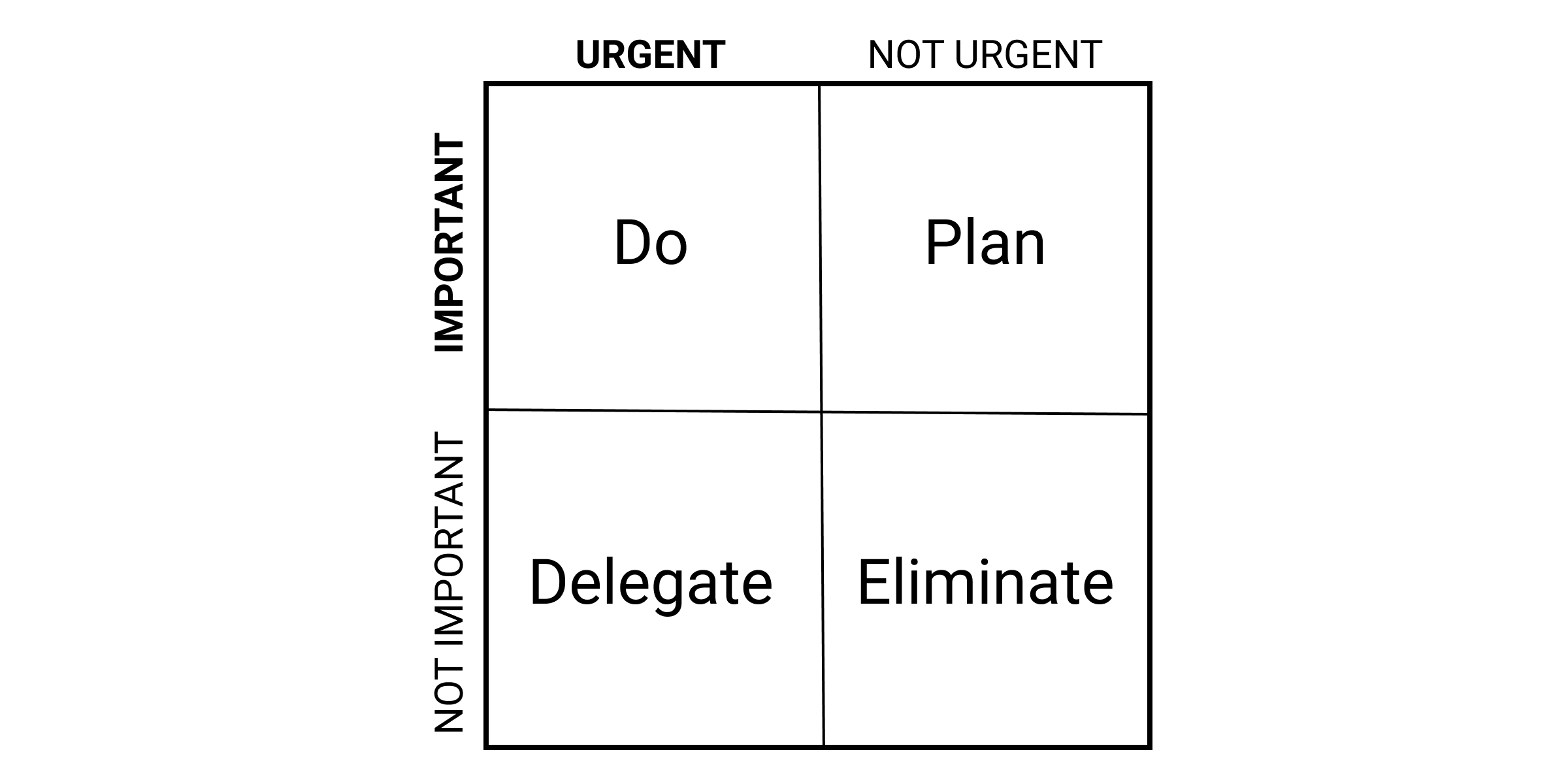

The Eisenhower Prioritization Matrix is a conceptual tool for time management that can help people decide what to work on. It’s a 2x2 matrix with urgency on one axis and importance on the other.

Urgent and important tasks, the thinking goes, should be done right away. Non-urgent but important tasks should be scheduled. Urgent and unimportant tasks should be delegated. And non-urgent, unimportant tasks shouldn’t be done at all.

The insight behind this matrix is that people often spend too much time on urgent tasks and not enough time on important tasks. So by delegating urgent but unimportant tasks, you can free up time for important things you might not get to otherwise.

I’ve found this tool to be helpful in reminding me to focus on what’s important. But it doesn’t address another problem I have: even if I’m only working on what’s important, always starting with what’s most urgent can mean that I don’t have enough time for less urgent tasks. I’m too much of a perfectionist.

For example, when I start work in the morning, I almost always need to spend some time preparing for my meetings that day. This work is both urgent (they are happening today) and important (no one else can do it). So by the logic of the Eisenhower matrix, preparing for these meetings should be the first thing that I do.

But when I follow this reasoning, I often find myself putting too much time into the meeting prep. I might second-guess what I’m doing, spend too much time researching something tangential, or get distracted by a topic unlikely to come up in the meeting. So instead of always prioritizing what's most urgent first, I've learned to practice "strategic procrastination": purposely delaying urgent tasks to constrain the amount of time that I can spend on them.

For example, at the beginning of my morning at work, I might estimate how much time I’ll need to prepare for my meetings and then delay starting that work until I have exactly that amount of time left. Before then I’ll work on one of my other, less urgent tasks. In this way, I’m leveraging the urgency of a task to limit how much time I spend on it.

Strategic procrastination is also useful on longer time scales. When I have to prepare a presentation, for example, I often find myself wasting time on minor things, like tweaking formatting, instead of developing the core content. To avoid this I employ strategic procrastination. I delay starting work on the presentation until I have just enough time to complete it.

I sometimes adjust this method when the task requires creativity. Instead of completely delaying when I begin a task, I get started right away, but I do just enough to begin thinking about it. For a presentation, I might first spend 30 minutes writing a rough outline and then put the task aside for a few weeks. This gives me a chance to ruminate on it during downtime, and I often get ideas that I wouldn’t have gotten otherwise.

There is actually some experimental evidence behind my intuition that this approach can improve creativity. As described in this paper and in the book Originals (which also uses the term “strategic procrastination”), students who played video games for a moderate amount of time while working on business problems came up with more creative solutions.

Strategic procrastination comes with a major risk, of course. There’s a reason that it’s usually considered good advice to not wait until the last minute to do things. If I misestimate how much time I need to perform a task, then I either need to scramble to complete it or the quality will suffer. So strategic procrastination is only a good idea when I’m confident about long it will take or if it’s not a big deal to underperform.

As long as I consider this risk, strategic procrastination has been a helpful tool to make sure I have enough time for important but non-urgent tasks. Sometimes waiting until the last minute is exactly what makes me the most productive.